Shaders

As mentioned in the Hello Triangle tutorial, shaders are little programs running on the GPU. These programs are run for each specific section of the graphics pipeline. In a basic sense, shaders are nothing more than programs transforming inputs to outputs. Shaders are also very isolated programs in that they’re not allowed to communicate with each other; the only communication they have is via their inputs and outputs.

In the previous tutorial we briefly touched the surface of shaders and how to properly use them. We will now explain shaders, and specifically the OpenGL Shading Language, in a more general fashion.

GLSL

Shaders are written in the C-like language GLSL. GLSL is tailored for use with graphics and contains useful features specifically targeted at vector and matrix manipulation.

Shaders always begin with a version declaration, followed by a list of input and output variables, uniforms and its main function. Each shader’s entry point is at its main function where we process any input variables and output the results in its output variables. Don’t worry if you don’t know what uniforms are, we’ll get to those shortly.

A shader typically has the following structure:

#version version_number

in type in_variable_name;

in type in_variable_name;

out type out_variable_name;

uniform type uniform_name;

void main()

{

// Process input(s) and do some weird graphics stuff

...

// Output processed stuff to output variable

out_variable_name = weird_stuff_we_processed;

}When we’re talking specifically about the vertex shader each input variable is also known as a vertex attribute. There is a maximum number of vertex attributes we’re allowed to declare limited by the hardware. OpenGL guarantees there are always at least 16 four-component vertex attributes available, but some hardware might allow for more which you can retrieve by querying GL_MAX_VERTEX_ATTRIBS:

var nrAttributes:GLint = 0

glGetIntegerv(GL_MAX_VERTEX_ATTRIBS, &nrAttributes)

print("Maximum nr of vertex attributes supported: \(nrAttributes)")This often returns the minimum of 16 which should be more than enough for most purposes.

Vectors

GLSL has like any other programming language data types for specifying what kind of variable we want to work with. GLSL has most of the default basic types we know from languages like C: int, float, double, uint and bool. GLSL also features two container types that we’ll be using a lot throughout the tutorials, namely vectors and matrices. We’ll discuss matrices in a later tutorial.

A vector in GLSL is a 1, 2, 3, or 4 component container for any of the basic types just mentioned. They can take the following form (n represents the number of components):

vecn: the default vector of n floats.bvecn: a vector of n booleans.ivecn: a vector of n integers.uvecn: a vector of n unsigned integers.dvecn: a vector of n double components.

Most of the time we will be using the basic vecn since floats are sufficient for most of our purposes.

Components of a vector can be accessed via vec.x where x is the first component of the vector. You can use .x, .y, .z and .w to access their first, second, third and fourth component respectively. GLSL also allows you to use rgba for colors or stpq for texture coordinates, accessing the same components.

The vector datatype allows for some interesting and flexible component selection called swizzling. Swizzling allows for the following syntax:

vec2 someVec;

vec4 differentVec = someVec.xyxx;

vec3 anotherVec = differentVec.zyw;

vec4 otherVec = someVec.xxxx + anotherVec.yxzy;You can use any combination of up to 4 letters to create a new vector (of the same type) as long as the original vector has those components; it is not allowed to access the .z component of a vec2 for example. We can also pass vectors as arguments to different vector constructor calls, reducing the number of arguments required:

vec2 vect = vec2(0.5f, 0.7f);

vec4 result = vec4(vect, 0.0f, 0.0f);

vec4 otherResult = vec4(result.xyz, 1.0f);Vectors are thus a flexible datatype that we can use for all kinds of input and output. Throughout the tutorials you’ll see plenty of examples of how we can creatively manage vectors.

Ins and outs

Shaders are nice little programs on their own, but they are part of a whole and for that reason we want to have inputs and outputs on the individual shaders so that we can move stuff around. GLSL defined the in and out keywords specifically for that purpose. Each shader can specify inputs and outputs using those keywords and wherever an output variable matches with an input variable of the next shader stage they’re passed along. The vertex and fragment shader differ a bit though.

The vertex shader should receive some form of input otherwise it would be pretty ineffective. The vertex shader differs in its input, in that it receives its input straight from the vertex data. To define how the vertex data is organized we specify the input variables with location metadata so we can configure the vertex attributes on the CPU. We’ve seen this in the previous tutorial as layout (location = 0). The vertex shader thus requires an extra layout specification for its inputs so we can link it with the vertex data.

It is also possible to omit the layout (location = 0) specifier and query for the attribute locations in your OpenGL code via glGetAttribLocation, but I’d prefer to set them in the vertex shader. It is easier to understand and saves you (and OpenGL) some work.

The other exception is that the fragment shader requires a vec4 color output variable, since the fragment shaders needs to generate a final output color. If you fail to specify an output color in your fragment shader OpenGL will render your object black (or white).

So if we want to send data from one shader to the other we’d have to declare an output in the sending shader and a similar input in the receiving shader. When the types and the names are equal on both sides OpenGL will link those variables together and then it is possible to send data between shaders (this is done when linking a program object). To show you how this works in practice we’re going to alter the shaders from the previous tutorial to let the vertex shader decide the color for the fragment shader.

Vertex shader

#version 330 core

layout (location = 0) in vec3 position; // The position variable has attribute position 0

out vec4 vertexColor; // Specify a color output to the fragment shader

void main()

{

gl_Position = vec4(position, 1.0); // See how we directly give a vec3 to vec4's constructor

vertexColor = vec4(0.5f, 0.0f, 0.0f, 1.0f); // Set the output variable to a dark-red color

}Fragment shader

#version 330 core

in vec4 vertexColor; // The input variable from the vertex shader (same name and same type)

out vec4 color;

void main()

{

color = vertexColor;

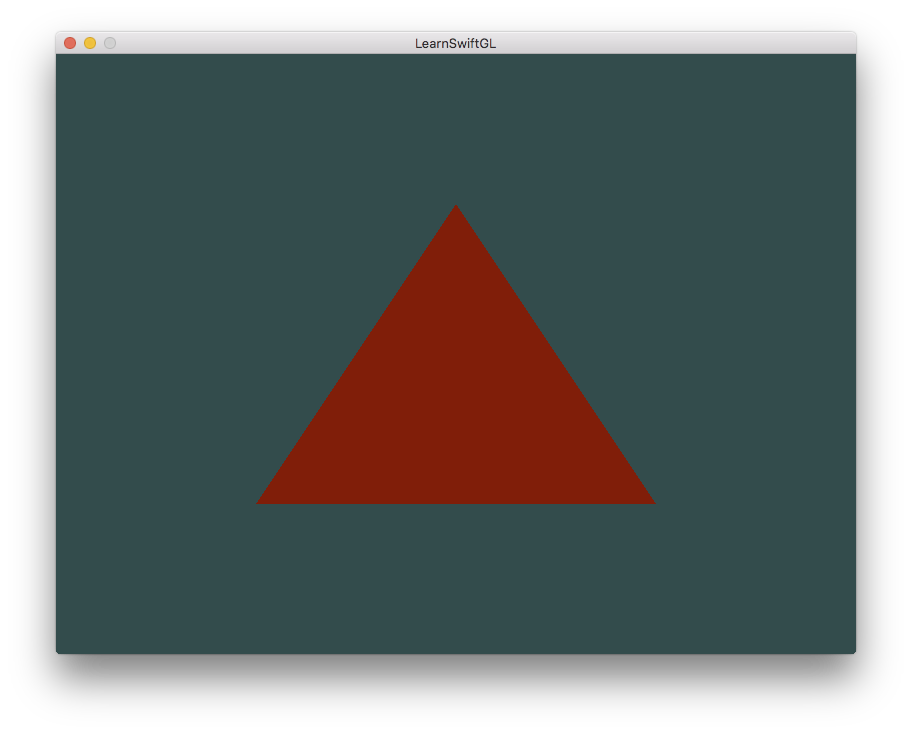

} You can see we declared a vertexColor variable as a vec4 output that we set in the vertex shader and we declare a similar vertexColor input in the fragment shader. Since they both have the same type and name, the vertexColor in the fragment shader is linked to the vertexColor in the vertex shader. Because we set the color to a dark-red color in the vertex shader, the resulting fragments should be dark-red as well. The following image shows the output:

There we go! We just managed to send a value from the vertex shader to the fragment shader. Let’s spice it up a bit and see if we can send a color from our application to the fragment shader!

Uniforms

Uniforms are another way to pass data from our application on the CPU to the shaders on the GPU, but uniforms are slightly different compared to vertex attributes. First of all, uniforms are global. Global, meaning that a uniform variable is unique per shader program object, and can be accessed from any shader at any stage in the shader program. Second, whatever you set the uniform value to, uniforms will keep their values until they’re either reset or updated.

To declare a uniform in GLSL we simply add the uniform keyword to a shader with a type and a name. From that point on we can use the newly declared uniform in the shader. Let’s see if this time we can set the color of the triangle via a uniform:

#version 330 core

out vec4 color;

uniform vec4 ourColor; // We set this variable in Swift code.

void main()

{

color = ourColor;

}We declared a uniform vec4 ourColor in the fragment shader and set the fragment’s output color to the content of this uniform value. Since uniforms are global variables, we can define them in any shader we’d like so no need to go through the vertex shader again to get something to the fragment shader. We’re not using this uniform in the vertex shader so there’s no need to define it there.

If you declare a uniform that isn’t used anywhere in your GLSL code the compiler will silently remove the variable from the compiled version which is the cause for several frustrating errors; keep this in mind!

The uniform is currently empty; we haven’t added any data to the uniform yet so let’s try that. We first need to find the index/location of the uniform attribute in our shader. Once we have the index/location of the uniform, we can update its values. Instead of passing a single color to the fragment shader, let’s spice things up by gradually changing color over time:

// At the top with the other imports. We need sin().

#if os(Linux)

import Glibc

#else

import Darwin.C

#endif

// In the game loop:

let timeValue = glfwGetTime()

let greenValue = (sin(timeValue) / 2) + 0.5

let vertexColorLocation = glGetUniformLocation(shaderProgram, "ourColor")

glUseProgram(shaderProgram)

glUniform4f(vertexColorLocation, 0.0, Float(greenValue), 0.0, 1.0)First, we retrieve the running time in seconds via glfwGetTime(). Then we vary the color in the range of 0.0 - 1.0 by using the sin function and store the result in greenValue.

Then we query for the location of the ourColor uniform using glGetUniformLocation. We supply the shader program and the name of the uniform (that we want to retrieve the location from) to the query function. If glGetUniformLocation returns -1, it could not find the location. Lastly we can set the uniform value using the glUniform4f function. Note that finding the uniform location does not require you to use the shader program first, but updating a uniform does require you to first use the program (by calling glUseProgram), because it sets the uniform on the currently active shader program.

Because OpenGL is in its core a C library it does not have native support for type overloading, so wherever a function can be called with different types OpenGL defines new functions for each type required; glUniform is a perfect example of this. The function requires a specific postfix for the type of the uniform you want to set. A few of the possible postfixes are:

- f: the function expects a float as its value

- i: the function expects an int as its value

- ui: the function expects an unsigned int as its value

- 3f: the function expects 3 floats as its value

- fv: the function expects a float vector/array as its value

Whenever you want to configure an option of OpenGL simply pick the overloaded function that corresponds with your type. In our case we want to set 4 floats of the uniform individually so we pass our data via glUniform4f (note that we also could’ve used the fv version).

Now what we know how to set the values of uniform variables, we can use them for rendering. If we want the color to gradually change, we want to update this uniform every game loop iteration (so it changes per-frame) otherwise the triangle would maintain a single solid color if we only set it once. So we calculate the greenValue and update the uniform each render iteration:

while(!glfwWindowShouldClose(window))

{

while glfwWindowShouldClose(window) == GL_FALSE

{

// Check if any events have been activated

// (key pressed, mouse moved etc.) and call

// the corresponding response functions

glfwPollEvents()

// Render

// Clear the colorbuffer

glClearColor(red: 0.2, green: 0.3, blue: 0.3, alpha: 1.0)

glClear(GL_COLOR_BUFFER_BIT)

// Draw our first triangle

glUseProgram(shaderProgram)

// Update the uniform color

let timeValue = glfwGetTime()

let greenValue = (sin(timeValue) / 2) + 0.5

let vertexColorLocation = glGetUniformLocation(shaderProgram, "ourColor")

glUniform4f(vertexColorLocation, 0.0, Float(greenValue), 0.0, 1.0)

glBindVertexArray(VAO)

glDrawArrays(GL_TRIANGLES, 0, 3)

glBindVertexArray(0)

// Swap the screen buffers

glfwSwapBuffers(window)

}The code is a relatively straightforward adaptation of the previous code. This time, we update a uniform value each iteration before drawing the triangle. If you update the uniform correctly you should see the color of your triangle gradually change from green to black and back to green.

Check out the source code here if you’re stuck.

As you can see, uniforms are a useful tool for setting attributes that might change in render iterations, or for interchanging data between your application and your shaders, but what if we want to set a color for each vertex? In that case we’d have to declare as many uniforms as we have vertices. A better solution would be to include more data in the vertex attributes which is what we’re going to do.

More attributes!

We saw in the previous tutorial how we can fill a VBO, configure vertex attribute pointers and store it all in a VAO. This time, we also want to add color data to the vertex data. We’re going to add color data as 3 floats to the vertices array. We assign a red, green and blue color to each of the corners of our triangle respectively:

let vertices:[GLfloat] = [

0.5, -0.5, 0.0, 1.0, 0.0, 0.0,// Bottom Right

-0.5, -0.5, 0.0, 0.0, 1.0, 0.0,// Bottom Left

0.0, 0.5, 0.0, 0.0, 0.0, 1.0 // Top

]Since we now have more data to send to the vertex shader, it is necessary to adjust the vertex shader to also receive our color value as a vertex attribute input. Note that we set the location of the color attribute to 1 with the layout specifier:

#version 330 core

layout (location = 0) in vec3 position; // The position variable has attribute position 0

layout (location = 1) in vec3 color; // The color variable has attribute position 1

out vec3 ourColor; // Output a color to the fragment shader

void main()

{

gl_Position = vec4(position, 1.0);

ourColor = color; // Set ourColor to the input color we got from the vertex data

} Since we no longer use a uniform for the fragment’s color, but now use the ourColor output variable we’ll have to change the fragment shader as well:

#version 330 core

in vec3 ourColor;

out vec4 color;

void main()

{

color = vec4(ourColor, 1.0f);

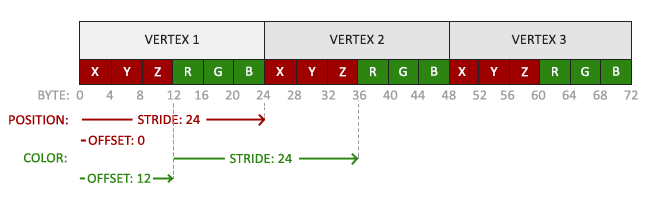

}Because we added another vertex attribute and updated the VBO’s memory we have to re-configure the vertex attribute pointers. The updated data in the VBO’s memory now looks a bit like this:

Knowing the current layout we can update the vertex format with glVertexAttribPointer:

// Position attribute

let pointer0offset = UnsafePointer<Void>(bitPattern: 0)

glVertexAttribPointer(index: 0, size: 3, type: GL_FLOAT,

normalized: false, stride: GLsizei(strideof(GLfloat) * 6), pointer: pointer0offset)

glEnableVertexAttribArray(0)

// Color attribute

let pointer1offset = UnsafePointer<Void>(bitPattern: strideof(GLfloat) * 3)

glVertexAttribPointer(index: 1, size: 3, type: GL_FLOAT,

normalized: false, stride: GLsizei(strideof(GLfloat) * 6), pointer: pointer1offset)

glEnableVertexAttribArray(1)The first few arguments of glVertexAttribPointer are relatively straightforward. This time we are configuring the vertex attribute on attribute location 1. The color values have a size of 3 floats and we do not normalize the values.

Since we now have two vertex attributes we have to re-calculate the stride value. To get the next attribute value (e.g. the next x component of the position vector) in the data array we have to move 6 floats to the right, three for the position values and three for the color values. This gives us a stride value of 6 times the size of a GLFloat in bytes (24 bytes).

Also, this time we have to specify an offset. For each vertex, the position vertex attribute is first so we declare an offset of 0. The color attribute starts after the position data so the offset is strideof(GLfloat) * 3 in bytes (12 bytes).

glVertexAttribPointer wants the offset as a void * type. We have to turn our integer into an UnsafePointer<Void> to make this call. Calling it a pointer and using void * has got to be some kind of mistake or inside joke. It is most definitely not a pointer.

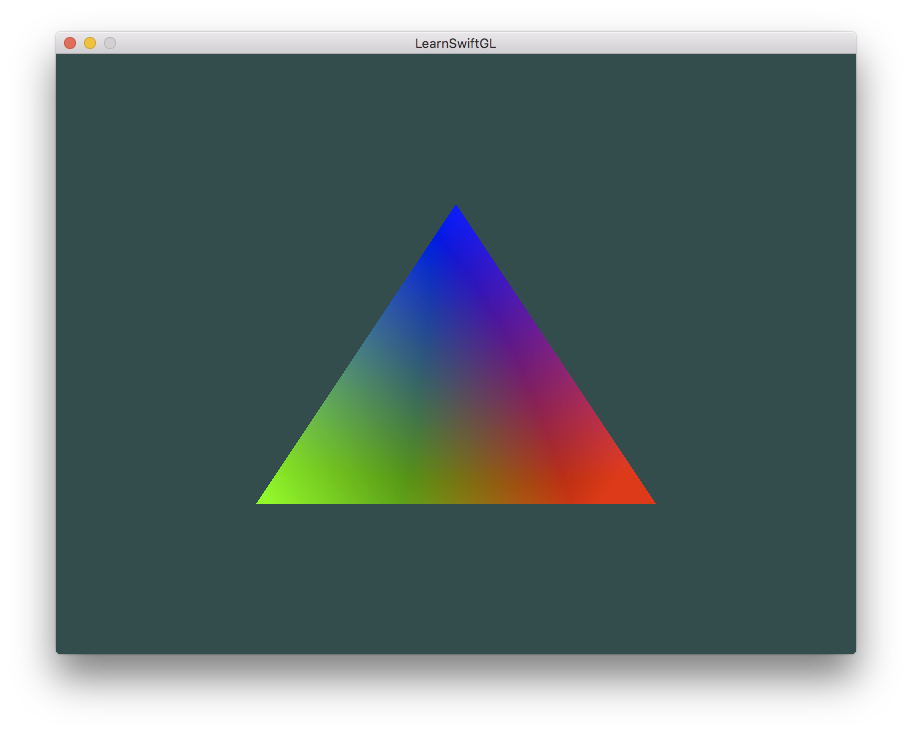

Running the application should result in the following image:

Check out the source code here if you’re stuck.

The image might not be exactly what you would expect, since we only supplied 3 colors, not the huge color palette we’re seeing right now. This is all the result of something called fragment interpolation in the fragment shader. When rendering a triangle the rasterization stage usually results in a lot more fragments than vertices originally specified. The rasterizer then determines the positions of each of those fragments based on where they reside on the triangle shape. Based on these positions, it interpolates all the fragment shader’s input variables. Say for example we have a line where the upper point has a green color and the lower point a blue color. If the fragment shader is run at a fragment that resides around a position at 70% of the line its resulting color input attribute would then be a linear combination of green and blue; to be more precise: 30% blue and 70% green.

This is exactly what happened at the triangle. We have 3 vertices and thus 3 colors and judging from the triangle’s pixels it probably contains around 50000 fragments, where the fragment shader interpolated the colors among those pixels. If you take a good look at the colors you’ll see it all makes sense: red to blue first gets to purple and then to blue. Fragment interpolation is applied to all the fragment shader’s input attributes.

Our own shader class

Writing, compiling and managing shaders can be quite cumbersome. As a final touch on the shader subject we’re going to make our life a bit easier by building a shader class that reads shaders from disk, compiles and links them, checks for errors and is easy to use. This also gives you a bit of an idea how we can encapsulate some of the knowledge we learned so far into useful abstract objects.

We will create the shader class entirely in a header file, mainly for learning purposes and portability. Let’s start by adding the required imports and by framing the class structure:

import Foundation

import SGLOpenGL

public class Shader {

public private(set) var program:GLuint = 0

public init(vertex:String, fragment:String)

{

// init from strings here

}

public convenience init(vertexFile:String, fragmentFile:String)

{

// init from files here

}

deinit

{

glDeleteProgram(program)

}

public func use()

{

glUseProgram(program)

}

}The shader class holds the ID of the shader program. The main initializer accepts strings for the vertex and fragment shaders. The convenience initializer requires file paths of the source code of the vertex and fragment shaders stored on disk as simple text files. The deinitializer will delete the shader program when Swift deletes this object. To add a little extra we also added a utility use function which is rather trivial, but a nice display of how we could ease our life (albeit a little) with homemade classes.

Compile and link

The bulk of the work is done with two static functions. What will happen is we call compileShader or linkProgram which, if an error is detected, fetches and returns the error as a String. We’ve enhanced things a bit to fetch the actual length of the error log message instead of simply allocating 512 bytes which would truncate anything longer.

private static func compileShader(shader: GLuint, source: String) -> String?

{

source.withCString {

var s = [$0]

glShaderSource(shader: shader, count: 1, string: &s, length: nil)

}

glCompileShader(shader)

var success:GLint = 0

glGetShaderiv(shader: shader, pname: GL_COMPILE_STATUS, params: &success)

if success != GL_TRUE {

var logSize:GLint = 0

glGetShaderiv(shader: shader, pname: GL_INFO_LOG_LENGTH, params: &logSize)

if logSize == 0 { return "" }

var infoLog = [GLchar](count: Int(logSize), repeatedValue: 0)

glGetShaderInfoLog(shader: shader, bufSize: logSize, length: nil, infoLog: &infoLog)

return String.fromCString(infoLog)!

}

return nil

}

private static func linkProgram(program: GLuint, vertex: GLuint, fragment: GLuint) -> String?

{

glAttachShader(program, vertex)

glAttachShader(program, fragment)

glLinkProgram(program)

var success:GLint = 0

glGetProgramiv(program: program, pname: GL_LINK_STATUS, params: &success)

if success != GL_TRUE {

var logSize:GLint = 0

glGetProgramiv(program: program, pname: GL_INFO_LOG_LENGTH, params: &logSize)

if logSize == 0 { return "" }

var infoLog = [GLchar](count: Int(logSize), repeatedValue: 0)

glGetProgramInfoLog(program: program, bufSize: logSize, length: nil, infoLog: &infoLog)

return String.fromCString(infoLog)!

}

return nil

}Initialization

Managing large shaders with string concatenation in a swift source file is tedious and leaves you with a hard to read shader. We want to write our shaders as their own source files instead. We’ll write a convenience initializer that accepts filenames, prepares strings with the contents of those files, and calls the designated initializer. If there’s any errors reading the files they are caught and printed in a fatalError.

First, we’ll use NSData from Foundation to load the files into memory. The regular String in Swift doesn’t know anything about Foundation so next we use NSString to convert the raw data into a string. Finally, we construct a String from NSString to call the designated initializer.

public convenience init(vertexFile:String, fragmentFile:String)

{

do {

let vertexData = try NSData(contentsOfFile: vertexFile,

options: [.DataReadingUncached, .DataReadingMappedAlways])

let fragmentData = try NSData(contentsOfFile: fragmentFile,

options: [.DataReadingUncached, .DataReadingMappedAlways])

let vertexString = NSString(data: vertexData, encoding: NSUTF8StringEncoding)

let fragmentString = NSString(data: fragmentData, encoding: NSUTF8StringEncoding)

self.init(vertex: String(vertexString!), fragment: String(fragmentString!))

}

catch let error as NSError {

fatalError(error.localizedFailureReason!)

}

}The designated initializer accepts two strings which have the shader source code as their content. It compiles both shaders and links them into the program. If any errors are detected, they are printed as a fatalError.

public init(vertex:String, fragment:String)

{

let vertexID = glCreateShader(type: GL_VERTEX_SHADER)

defer{ glDeleteShader(vertexID) }

if let errorMessage = Shader.compileShader(vertexID, source: vertex) {

fatalError(errorMessage)

}

let fragmentID = glCreateShader(type: GL_FRAGMENT_SHADER)

defer{ glDeleteShader(fragmentID) }

if let errorMessage = Shader.compileShader(fragmentID, source: fragment) {

fatalError(errorMessage)

}

self.program = glCreateProgram()

if let errorMessage = Shader.linkProgram(program, vertex: vertexID, fragment: fragmentID) {

fatalError(errorMessage)

}

}And there we have it, a completed shader class. Using the shader class is fairly easy; we create a shader object once and from that point on simply start using it:

let ourShader = Shader(vertexFile: "basic.vs", fragmentFile: "basic.frag")

while glfwWindowShouldClose(window) == GL_FALSE

{

//...

ourShader.use()

drawStuff()

//...

}Here we stored the vertex and fragment shader source code in two files called shader.vs and shader.frag. You’re free to name your shader files in any way you like; I personally find the extensions .vs and .frag quite intuitive.

Source code of the program using the new shader class, the shader class, the vertex shader and the fragment shader.

Exercises

- Adjust the vertex shader so that the triangle is upside down.

- Specify a horizontal offset via a uniform and move the triangle to the right side of the screen in the vertex shader using this offset value.

- Output the vertex position to the fragment shader using the out keyword and set the fragment’s color equal to this vertex position (see how even the vertex position values are interpolated across the triangle). Once you managed to do this; try to answer the following question: why is the bottom-left side of our triangle black?